Medieval monks transformed European winemaking through systematic vineyard cultivation across Burgundy, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, driven by religious requirements for Mass and institutional resources from noble land grants. Benedictine and Cistercian orders developed foundational concepts like terroir, implemented grape sorting and blending techniques, and preserved viticultural knowledge through libraries and training programs during periods of political instability. Notable innovations include Dom Pérignon‘s sparkling wine refinements at Hautvillers and Benedictine nuns creating vin jaune in Jura, establishing quality standards that made wines commercially viable by the 15th century and shaped regions still celebrated today.

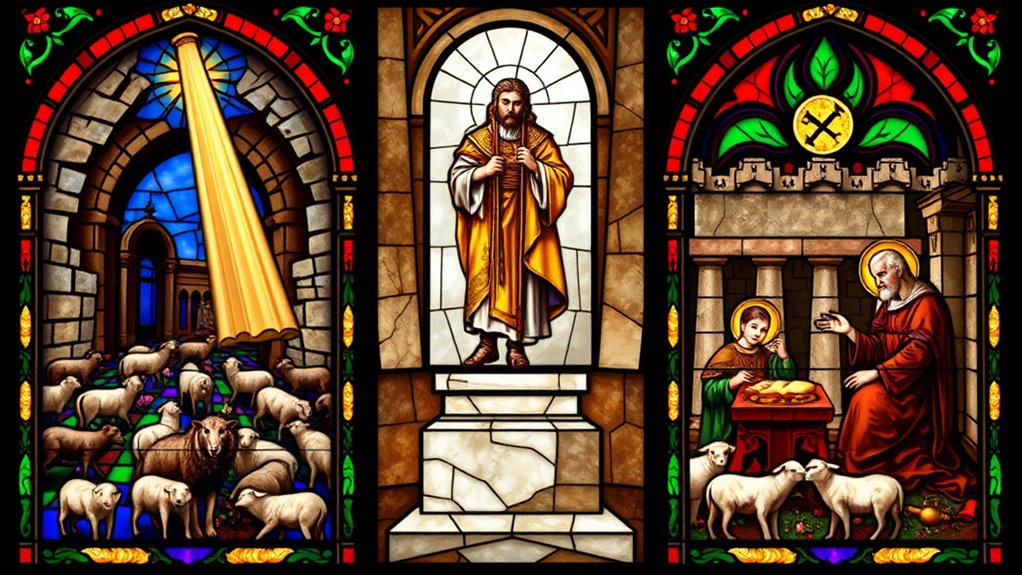

For more than a thousand years, European monks transformed winemaking from a simple agricultural practice into a sophisticated craft that would shape the continent’s cultural and economic landscape. What began as a religious necessity—producing wine for the Catholic Mass and Eucharist—evolved into an enterprise that established many of Europe’s most celebrated wine regions and advanced viticulture techniques that endure today.

Monasteries required consistent wine supplies for religious rituals, making viticulture essential to monastic life. Nobility endowed abbeys with land and vineyards in exchange for prayers, economic prosperity, and education, providing monks with resources to develop their craft. Religious commitment motivated these communities to pursue viticultural excellence more thoroughly than perhaps any other group in history, driven by both spiritual devotion and the practical need for self-sufficiency during the early Middle Ages.

Spiritual devotion and practical necessity drove monks to pursue viticultural excellence more thoroughly than perhaps any other group in medieval history.

Benedictine and Cistercian monks established vineyards across Burgundy, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, planting vines in regions that remain major producers today. The Cistercians founded approximately 120 convents in Portugal and became primary keepers of agricultural knowledge by the late 12th century. The Abbey of Saint-Vivant cleared woodland and planted vines in Vosne, establishing what became the grand cru Romanée-Saint-Vivant. At Pontigny Abbey, monks developed the vineyards of Chablis, while other orders cultivated Sauvignon Blanc regions in Quincy. Monastic libraries and scriptoria also preserved agricultural treatises that helped spread viticultural knowledge across Europe.

Beyond establishing vineyards, monastic communities preserved and advanced winemaking techniques during medieval periods characterized by war and instability. The concept of terroir—understanding how land influences wine—truly came into being under monastic stewardship. Monks implemented careful grape sorting and blending practices, ensuring only the best grapes reached production. By the 15th century, quality improvements made wines suitable for commercial sale. Cistercians provided training to congregations on vine growing and winemaking, spreading viticultural knowledge beyond monastery walls. Wine also served as medicine and daily sustenance for monks, pilgrims, students, and the sick within monastery walls.

Notable innovations emerged from these religious communities. Dom Perignon, a blind Benedictine monk at the Abbey of Hautvillers around 1668, refined the art of making white wine from black grapes and advanced sparkling wine production techniques that helped Champagne achieve continental success by the 1800s. Benedictine nuns at the Abbey of Château Chalon developed Jura’s distinctive vin jaune and vin de paille, demonstrating the breadth of monastic contributions to European wine culture.