St. Francis Xavier, a Spanish nobleman and founding Jesuit, arrived in Portuguese Goa in 1542 to revitalize Christianity across Asia. He learned local dialects, built nearly ninety churches from Cape Comorin to Travancore, and baptized thousands despite opposition from established religious communities and colonial exploitation he openly condemned. His eleven-year mission extended to Malacca and the Maluku Islands, establishing a Catholic presence that grew to 10,000 adherents by the 1560s. Xavier founded seminaries, trained native priests, and created institutional structures that outlasted empires, earning recognition as patron of foreign missions for transforming the region’s spiritual landscape.

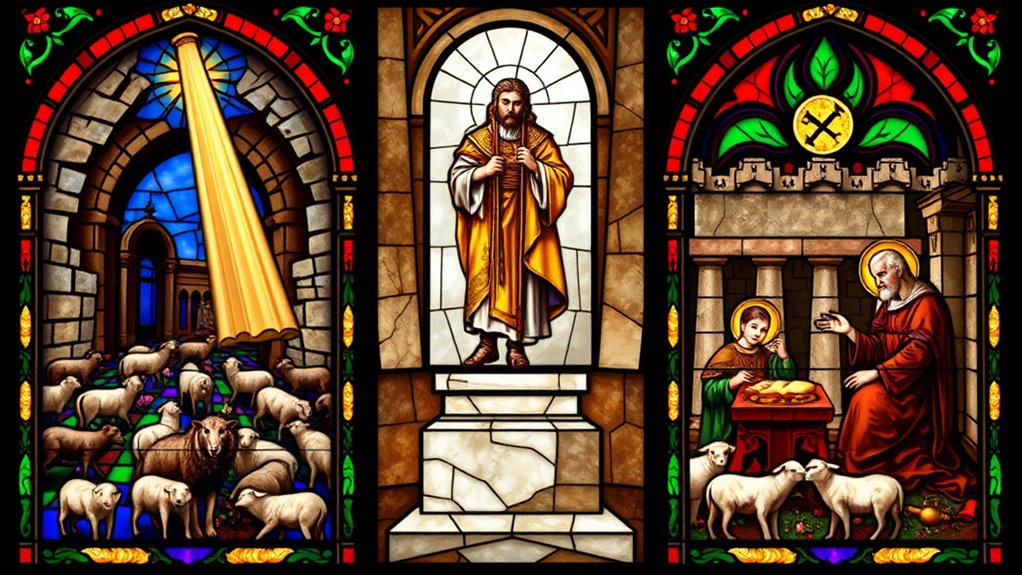

In 1542, when a Spanish nobleman stepped off a Portuguese ship onto the shores of Goa, India, he carried little more than his priestly robes and an unshakeable conviction that would reshape the spiritual landscape of South and Southeast Asia. His methods have been examined alongside broader historical interpretations of ministry roles in church history. Francis Xavier, born in 1506 in the Kingdom of Navarre, had already earned a master’s degree from the University of Paris and joined Ignatius of Loyola’s newly formed Society of Jesus in 1534.

Armed with nothing but faith and determination, one man’s arrival in 1542 would forever transform Asia’s spiritual destiny.

When King John III of Portugal requested priests for evangelization in the East Indies, Xavier offered his services after war blocked his original plans for the Middle East.

The year-long voyage from Lisbon included stops in Mozambique and Melindi for preaching before Xavier arrived in Goa on May 6, 1542. He found a complacent Christian community requiring revitalization, gathering children with a bell for catechism instruction while preaching to the sick in hospitals. His work provided a counterexample to the poor behavior of Portuguese sailors who often exploited local populations.

In October 1542, Xavier traveled to Cape Comorin to serve the Paravas community, who had been baptized a decade earlier but never instructed in Christian doctrine. He learned their language, taught both the previously baptized and new converts, and built nearly forty churches from Cape Comorin to Mannar over three years. His missions extended into Travancore, where he founded forty-five additional churches, though he faced opposition from Brahmins and Muslims that sometimes resulted in massacres of converts. Xavier communicated through translated catechisms while adapting to local cultural practices.

Xavier’s influence reached beyond India to Malacca and the Maluku Islands between 1546 and 1547, where he established foundations in Ambon, Ternate, and Morotai. By the 1560s, these regions counted ten thousand Catholics. Reports described him baptizing so many people that his arms grew weary, and locals called him Great Father. In 1548, he founded a Jesuit novitiate and recruited native priests to strengthen the institutional foundation of his missionary work.

The Holy See later named him patron of foreign missions, recognizing how his eleven years of work created permanent institutional changes across South and Southeast Asia. Xavier died in 1552, having transformed Christianity’s presence in the region through persistent effort and systematic foundation-building.