The Virgin of Guadalupe’s appearance on Juan Diego’s tilma in December 1531 transformed Catholic worship across the Americas by intertwining Marian devotion with Eucharistic practice. The miraculous image, displayed at Tepeyac Hill where pilgrims gathered in growing numbers, became central to liturgical processions that emphasized sacramental theology. Franciscan missionaries and diocesan authorities promoted this dual focus, using the image as visual catechesis that connected indigenous populations to both the Virgin and the Eucharist. This integration reshaped religious life throughout New Spain, creating a devotional framework that linked reverence for Mary with renewed emphasis on the sacraments and extended the movement’s influence across colonial territories.

In December 1531, barely a decade after Spanish forces toppled the Aztec Empire, a cloth bearing the image of a dark-skinned Virgin appeared at Tepeyac Hill outside Mexico City, igniting a devotional movement that would reshape religious life across New Spain. Scholars note that contemporary Christian practice around burial practices influenced how indigenous communities integrated Marian veneration.

The image reportedly appeared on the agave-fiber cloak of Juan Diego, an indigenous convert, at a site previously associated with the Aztec mother-goddess Tonantzin. Within weeks, the local bishop placed the tilma on public display, and processions installed it at a chapel on Tepeyac, establishing a pilgrimage site that drew thousands.

The tilma’s rapid installation at Tepeyac transformed an ancient indigenous sacred site into a major Christian pilgrimage destination within weeks.

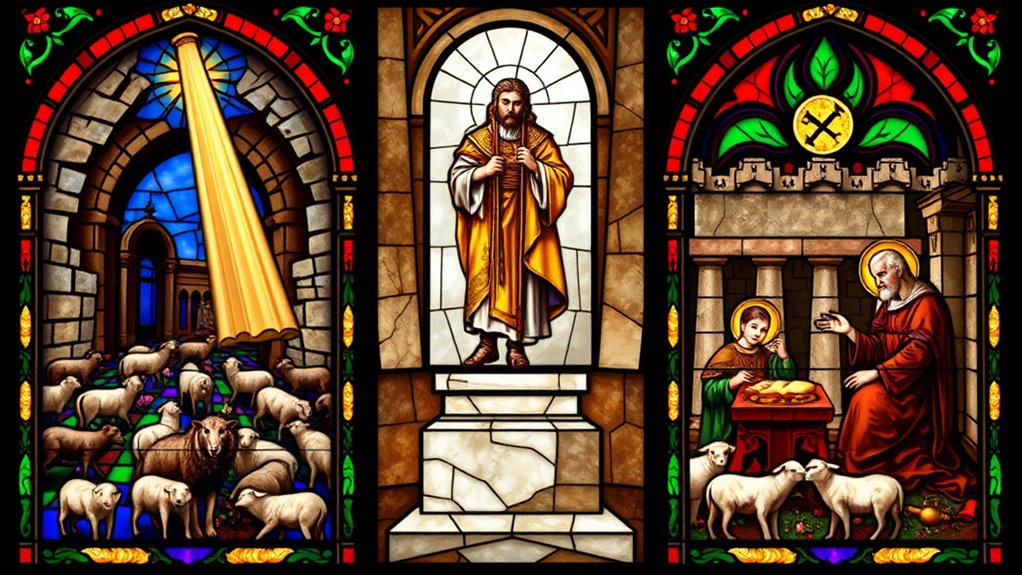

The image’s visual language bridged two worlds. The Virgin wore a blue-green mantle scattered with stars and stood before the sun with the moon at her feet, echoing both Revelation 12:1 and indigenous solar-lunar symbolism. A four-petaled flower marked her womb, and her mestiza features and native dress resonated with Nahua populations.

For largely illiterate communities, the image functioned as visual catechesis, conveying Christian theology through familiar motifs. This accessibility accelerated conversions as devotees recognized elements of pre-Hispanic devotion woven into Catholic Marian imagery.

Technical examinations have fueled ongoing debate. Proponents note the absence of conventional brush strokes and undersketch, describing the image as acheiropoieta—not made by human hands. The tilma’s survival for nearly five centuries, despite agave fiber typically degrading within decades, is cited as evidence of miraculous preservation.

Some devotional studies claim the mantle’s stars match the December 12, 1531 night sky, though these assertions remain contested in scientific circles.

The Guadalupe phenomenon coincided with mendicant orders and diocesan authorities intensifying Eucharistic piety across 16th and 17th-century New Spain. The Virgin’s image became central to communal liturgies and processions, linking Marian devotion to sacramental practice. Franciscan missionaries worked alongside diocesan clergy to incorporate the Guadalupan devotion into their broader efforts at evangelizing indigenous populations.

Early documentary sources, including the 16th-century Codex Escalada, framed the apparition as miraculous, reinforcing ecclesiastical endorsement. Clerical support transformed Tepeyac into a major devotional center, integrating the image into the machinery of evangelization. In 1556, Dominican Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar promoted devotion to the miraculous image on the cloth, shifting the shrine’s custody from Franciscans to diocesan priests and authorizing construction of a larger church at Tepeyac.

This syncretic reception, combining indigenous reverence and Catholic theology, catalyzed a eucharistic renewal that extended beyond Mexico’s borders, shaping religious identity throughout the Americas.