New Year’s resolutions trace back nearly 4,000 years to ancient Babylon, where citizens made promises to gods during the 12-day Akitu festival each spring, linking personal accountability to divine favor and good harvests. The Romans later shifted the practice to January 1 under Julius Caesar, naming the month after Janus, the two-faced god symbolizing reflection on the past and hopes for the future. Medieval knights renewed chivalric vows while Christians attended mass for spiritual renewal. Today, despite only 9% of Americans following through on their resolutions, the tradition endures as a symbol of self-improvement and fresh starts, with experts suggesting the key lies in understanding its historical roots and modern applications.

Every January, millions of people pledge to exercise more, save money, or break bad habits, continuing a tradition that stretches back thousands of years. The practice of making promises at the start of a new year began with the ancient Babylonians, who celebrated the Akitu festival for twelve days around March or April. This agricultural new year festival encouraged citizens to make promises to their gods, including returning borrowed tools and settling small debts, with kept promises ensuring good fortune in the coming harvest season. Some ancient and religious traditions also linked resolutions to sexual purity teachings that encouraged abstinence until marriage.

The Romans shifted the new year to January 1 in 46 B.C. under Julius Caesar, naming the month after Janus, the two-faced god who looked both backward and forward. Citizens offered sacrifices to Janus and made resolutions for good behavior, while government officials pledged loyalty to the emperor on this significant date. The connection between new beginnings and personal improvement had already taken root in ancient consciousness.

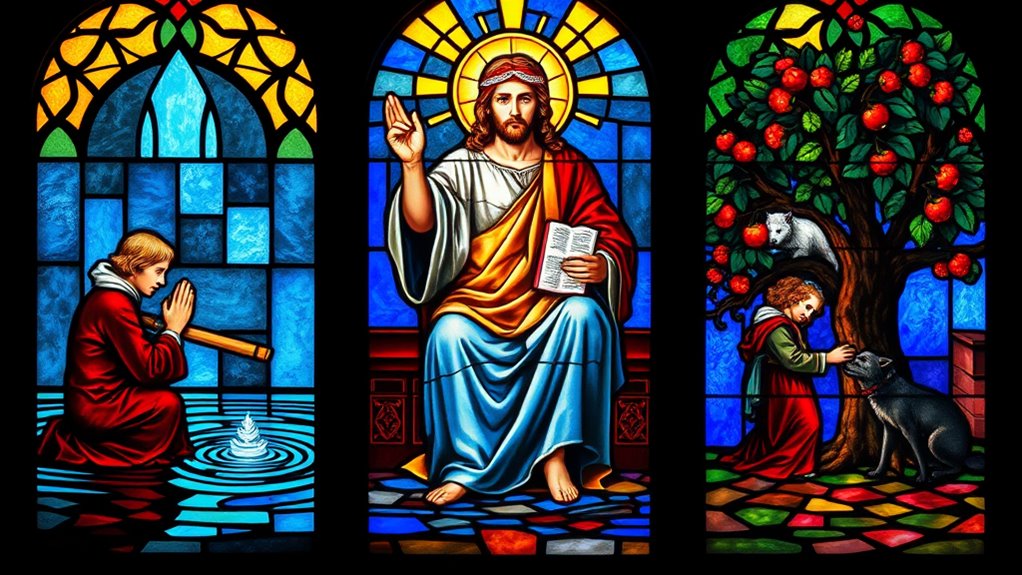

During the Middle Ages, the tradition continued through different forms. Knights took the annual Peacock Vow at year-end, placing their hands on a peacock to renew their chivalric values. Christians attended mass on New Year’s Eve or Day, using the occasion for reflection and resolving to improve in the coming year.

By the late seventeenth century, resolutions had become an established practice, as evidenced by Scottish writer Anne Halkett, who wrote resolutions on January 2, 1671, drawing from biblical verses like “I will not offend any more” on a page titled “Resolutions.”

The phrase “New Year resolution” first appeared in a 1813 Boston newspaper article called “The Friday Lecture,” which noted that people sinned in December expecting resolutions to expiate their faults. The practice was already being satirized by 1802 in Walker’s Hibernian Magazine with joke resolutions. Despite studies showing most resolutions fail, the tradition persists. Modern experts recommend starting with manageable goals and warming up in December to ease the transition into January routines.

The Times Square ball drop, which began in 1907 and originated from ancient sailing timekeeping practices, marks the moment when Americans renew their annual self-improvement attempts, a ritual as old as new year celebrations themselves. In the U.S., resolutions focus on health and personal improvement, yet only 9% follow through on their commitments.